Ajax Battle: XMLHttpRequest vs the Fetch API

Ajax is the core technology behind most web applications. It allows a page to make requests to a web service (or any external resource really) so data can be presented without a page-refreshing round-trip to the server.

The term Ajax is not a technology though; instead, it refers to techniques which can load server data from a client-side script without triggering a full-page refresh. Several options have been introduced over the years. Two primary methods remain, and most JavaScript frameworks will use one or both.

In this article we examine the pros and cons of the ancient XMLHttpRequest and its modern Fetch equivalent, to decide which Ajax API is best for you application.

XMLHttpRequest

XMLHttpRequest first appeared as a non-standard Internet Explorer 5.0 ActiveX component in 1999. Microsoft developed it to power their browser-based version of Outlook. XML was the most popular (or hyped) data format at the time, but XMLHttpRequest supported text and the yet-to-be-invented JSON.

Jesse James Garrett devised the term “AJAX” in his 2005 article AJAX: A New Approach to Web Applications. AJAX-based apps such as Gmail and Google Maps already existed, but the term galvanized developers and led to an explosion in slick Web 2.0 experiences.

AJAX is a mnemonic for “Asynchronous JavaScript and XML”, although, strictly speaking, developers didn’t need to use asynchronous methods, JavaScript, or XML. We now use the generic “Ajax” term for any client-side process that fetches data from a server and updates the DOM without requiring a full-page refresh.

XMLHttpRequest is supported by all mainstream browsers and became an official web standard in 2006.

The following is a simple example which fetches a resource (data) from your domain’s /service/ endpoint and displays the JSON result in the console as text:

const xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open("GET", "/service");

// state change event

xhr.onreadystatechange = () => {

// is request complete?

if (xhr.readyState !== 4) return;

if (xhr.status === 200) {

// request successful

console.log(JSON.parse(xhr.responseText));

} else {

// request not successful

console.log("HTTP error", xhr.status, xhr.statusText);

}

};

// start request

xhr.send();The onreadystatechange callback function runs several times throughout the lifecycle of the request. The XMLHttpRequest object’s readyState property returns the current state:

- 0 (uninitialized) - request not initialized

- 1 (loading) - server connection established

- 2 (loaded) - request received

- 3 (interactive) - processing request

- 4 (complete) - request complete, response is ready

Few functions do much until state 4 is reached. As you can see, using this method requires you to understand a little bit about the inner workings of HTTP and the different states within it.

Fetch

Fetch is a modern Promise-based Ajax request API that first appeared in 2015 and is supported in most browsers.

It is not built on XMLHttpRequest and offers better consistency with a more concise syntax. The following Promise chain functions identically to the XMLHttpRequest example above

when it comes to fetching a resource through a GET method:

fetch("/service", { method: "GET" })

.then((res) => res.json())

.then((json) => console.log(json))

.catch((err) => console.error("error:", err));Or you can use async / await:

try {

const res = await fetch("/service", { method: "GET" }),

json = await res.json();

console.log(json);

} catch (err) {

console.error("error:", err);

}Fetch is cleaner, simpler, and regularly used in Service Workers. With the Fetch API approach, you really only worry about the request you want to send, and the response you want to

get in return. The intricacies of HTTP are abstracted away.

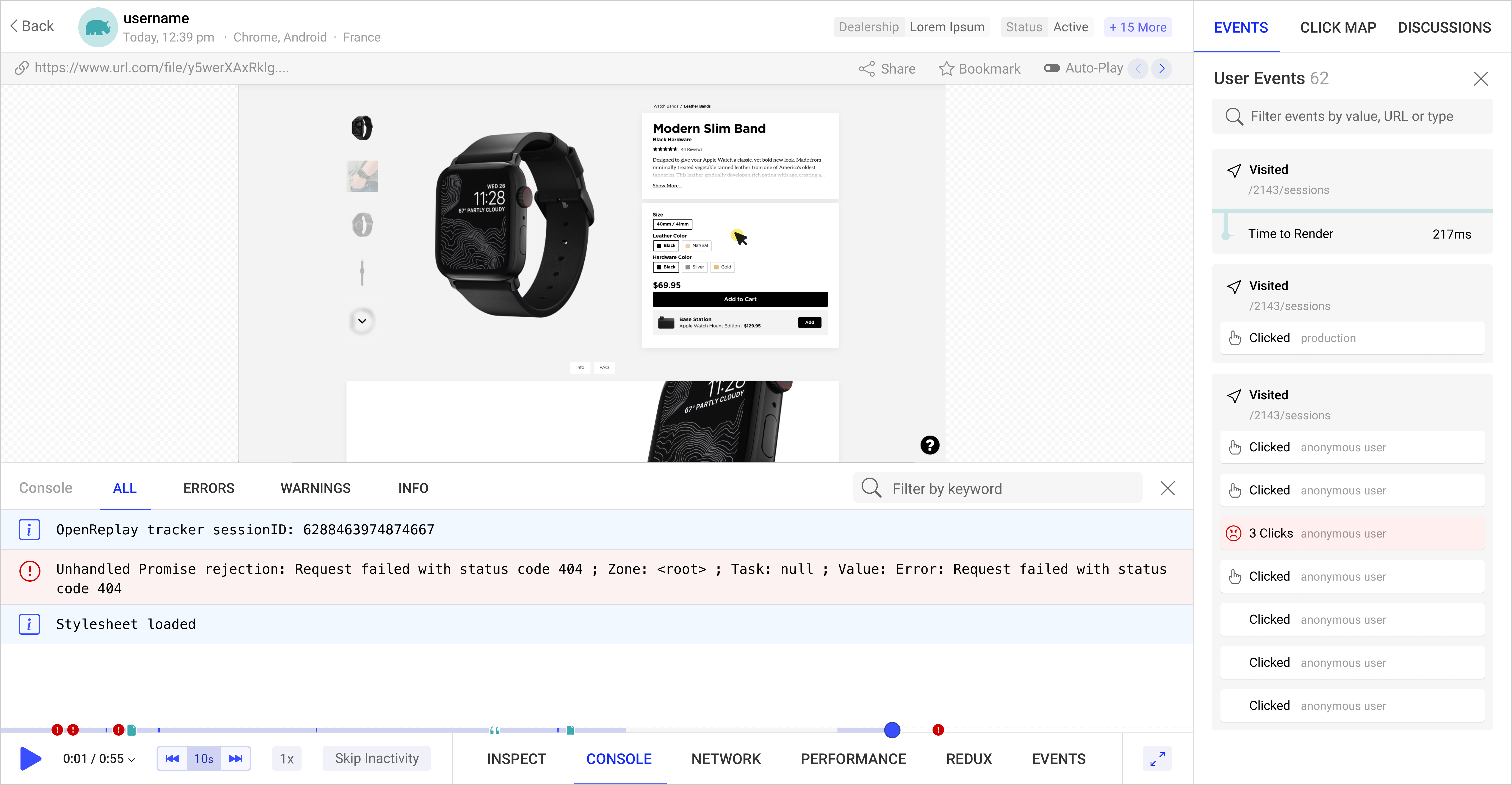

Open Source Session Replay

OpenReplay is an open-source, session replay suite that lets you see what users do on your web app, helping you troubleshoot issues faster. OpenReplay is self-hosted for full control over your data.

Start enjoying your debugging experience - start using OpenReplay for free.

Round 1: Fetch Wins

As well as a cleaner, more concise syntax, the Fetch API offers several advantages over the aging XMLHttpRequest.

Header, Request, and Response Objects

The simple fetch() example above uses a string to define an endpoint URL. A configurable Request object can also be passed, which provides a range of properties about the call:

const request = new Request("/service", { method: "POST" });

console.log(request.url);

console.log(request.method);

console.log(request.credentials);

// FormData representation of body

const fd = await request.formData();

// clone request

const req2 = request.clone();

const res = await fetch(request);The Response object provides similar access to all details of the response:

console.log(res.ok); // true/false

console.log(res.status); // HTTP status

console.log(res.url);

const json = await res.json(); // parses body as JSON

const text = await res.text(); // parses body as text

const fd = await res.formData(); // FormData representation of bodyA Headers object provides an easy interface to set headers in the Request or examine headers in the Response:

// set request headers

const headers = new Headers();

headers.set("X-Requested-With", "ajax");

headers.append("Content-Type", "text/xml");

const request = new Request("/service", {

method: "POST",

headers,

});

const res = await fetch(request);

// examine response headers

console.log(res.headers.get("Content-Type"));Caching Control

It’s challenging to manage caching in XMLHttpRequest, and you may find it necessary to append a random query string value to bypass the browser cache. Fetch offers built-in caching support in the second parameter init object:

const res = await fetch("/service", {

method: "GET",

cache: "default",

});

cache can be set to:

'default'- the browser cache is used if there’s a fresh (unexpired) match. If not, the browser makes a conditional request to check whether the resource has changed and makes a new request if necessary'no-store'- the browser cache is bypassed, and the network response will not update it'reload'- the browser cache is bypassed, but the network response will update it'no-cache'- similar to'default'except a conditional request is always made'force-cache'- the cached version is used if possible, even when it’s stale'only-if-cached'- identical toforce-cacheexcept no network request is made

CORS Control

Cross-Origin Resource Sharing allows a client-side script to make an Ajax request to another domain if that server permits the origin domain in the Access-Control-Allow-Origin response header. i

Both fetch() and XMLHttpRequest will fail when this is not set. However, Fetch provides a mode property which can be set to 'no-cors' in the second parameter init object:

const res = await fetch(

'https://anotherdomain.com/service',

{

method: 'GET',

mode: 'no-cors'

}

);This retrieves a response that cannot be read but can be used by other APIs. For example, you could use the Cache API to store the response and use it later, perhaps from a Service Worker to return an image, script, or CSS file.

Credential Control

XMLHttpRequest always sends browser cookies. The Fetch API does not send cookies unless you explicitly set a credentials property in the second parameter init object:

const res = await fetch("/service", {

method: "GET",

credentials: "same-origin",

});credentials can be set to:

'omit'- exclude cookies and HTTP authentication entries (the default)'same-origin'- include credentials with requests to same-origin URLs'include'- include credentials on all requests

Note that include was the default in earlier API implementations. Explicitly set the credentials property if your users are likely to run older browsers.

Redirect Control

By default, both fetch() and XMLHttpRequest follow server redirects. However, fetch() provides alternative options in the second parameter init object:

const res = await fetch("/service", {

method: "GET",

redirect: "follow",

});redirect can be set to:

'follow'- follow all redirects (the default)'error'- abort (reject) when a redirect occurs'manual'- return the response for manual handling

Data Streams

XMLHttpRequest reads the whole response into a memory buffer but fetch() can stream both request and response data. The technology is new, but streams allow you to work on smaller chunks of data as they are sent or received.

For example, you could process information in a multi-megabyte file before it is fully downloaded. The following example transforms incoming (binary) data chunks into text and outputs it to the console. On slower connections, you will see smaller chunks arriving over an extended period.

const response = await fetch("/service"),

reader = response.body

.pipeThrough(new TextDecoderStream())

.getReader();

while (true) {

const { value, done } = await reader.read();

if (done) break;

console.log(value);

}Server-Side Support

Fetch is fully supported in Deno and Node 18. Using the same API on both the server and the client helps reduce cognitive overhead and offers the possibility of isomorphic JavaScript libraries which work anywhere.

Round 2: XMLHttpRequest Wins

Despite a bruising, XMLHttpRequest has a few tricks to out-Ajax Fetch().

Progress Support

We may monitor the progress of requests by attaching a handler to the XMLHttpRequest object’s progress event. This is especially useful when uploading large files such as photographs, e.g.

const xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

// progress event

xhr.upload.onprogress = (p) => {

console.log(Math.round((p.loaded / p.total) * 100) + "%");

};The event handler is passed an object with three properties:

lengthComputable- settrueif the progress can be calculatedtotal- the total amount of work - orContent-Length- of the message bodyloaded- the amount of work - or content - completed so far

The Fetch API does not offer any way to monitor upload progress.

Timeout Support

The XMLHttpRequest object provides a timeout property which can be set to the number of milliseconds a request is permitted to run before it’s automatically terminated. A timeout event handler can also be triggered when this occurs:

const xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.timeout = 5000; // 5-second maximum

xhr.ontimeout = () => console.log("timeout");Wrapper functions can implement timeout functionality in a fetch():

function fetchTimeout(url, init, timeout = 5000) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

fetch(url, init).then(resolve).catch(reject);

setTimeout(reject, timeout);

});

}Alternatively, you could use Promise.race():

Promise.race([

fetch("/service", { method: "GET" }),

new Promise((resolve) => setTimeout(resolve, 5000)),

]).then((res) => console.log(res));Neither option is easy to use, and the request will continue in the background.

Abort Support

An in-flight request can be cancelled by running the XMLHttpRequest abort() method. An abort handler can be attached if necessary:

const xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open("GET", "/service");

xhr.send();

// ...

xhr.onabort = () => console.log("aborted");

xhr.abort();You can abort a fetch() but it’s not as straight-forward and requires a AbortController object:

const controller = new AbortController();

fetch("/service", {

method: "GET",

signal: controller.signal,

})

.then((res) => res.json())

.then((json) => console.log(json))

.catch((error) => console.error("Error:", error));

// abort request

controller.abort();The catch() block executes when the fetch() aborts.

More Obvious Failure Detection

When developers first use fetch(), it seems logical to presume that an HTTP error such as 404 Not Found or 500 Internal Server Error will trigger a Promise reject and run the associated catch() block. This is not the case: the Promise successfully resolves on any response. A rejection is only likely to occur when there’s no response from the network or the request is aborted.

The fetch() Response object provides status and ok properties, but it’s not always obvious they need to be checked. XMLHttpRequest is more explicit because a single callback function handles every outcome: you should see a status check in every example.

Browser Support

I hope you do not have to support Internet Explorer or browser versions prior to 2015, but if that’s the case, XMLHttpRequest is your only option. XMLHttpRequest is also stable, and the API is unlikely to be updated. Fetch is newer and missing several key features: updates are unlikely to break code, but you can expect some maintenance.

Which API Should You Use?

Most developers will reach for the more modern Fetch API. It has a cleaner syntax and more benefits over XMLHttpRequest.

That said, many of those benefits have niche use-cases, and you won’t require them in most applications. There are two occasions when XMLHttpRequest remains essential:

- You’re supporting very old browsers - that requirement should decline over time.

- You need to show upload progress bars.

Fetchwill gain support eventually, but it could be several years away.

Both alternatives are interesting, and it’s worth knowing them in detail!