An Introduction to JavaScript Error Handling - Making your applications more stable

Your apps become more robust as you gain programming experience. Improvements to coding techniques play a large part but you’ll also learn to consider the edge cases. If something can go wrong, it will go wrong: typically when the first user accesses your new system.

Some errors are avoidable:

-

A JavaScript linter or good editor can catch syntax errors such as misspelled statements and missing brackets.

-

You can use validation to catch errors in data from users or other systems. Never make presumptions about a user’s ingenuity to cause havoc. You may be expecting a numeric integer when asking for someone’s age but could they leave the box blank, enter a negative value, use a fractional value, or even fully type “twenty-one” in their native language.

Remember that server-side validation is essential. Browser-based client-side validation can improve the UI but the user could be using an application where JavaScript is disabled, fails to load, or fails to execute. It may not be a browser that’s calling your API!

Other runtime errors are impossible to avoid:

- the network can fail

- a busy server or application could take too long to respond

- a script or other asset could time out

- the application can fail

- a disk or database can fail

- a server OS can fail

- a host’s infrastructure can fail

These may be temporary. You cannot necessarily code your way out of these issues but you can anticipate problems, take appropriate actions, and make your application more resilient.

Showing an Error is the Last Resort

We’ve all encountered errors in applications. Some are useful:

“The file already exists. Would you like to overwrite it?”

Others are less so:

“ERROR 5969”

Showing an error to the user should be the last resort after exhausting all other options.

You may be able to ignore some less-critical errors such as an image failing to load. In other cases, remedial or recovery actions may be possible. For example, if you’re unable to save data to a server because of a network failure, you could temporarily store it in IndexedDB or localStorage and try a few minutes later. It should only be necessary to show a warning when repeated saves fail and the user is at risk of losing data. Even then: ensure the user can take appropriate actions. They may be able to reconnect to the network but that won’t help if your server is down.

Error Handling in JavaScript

Error handling is simple in JavaScript but it’s often shrouded in mystery and can become complicated when considering asynchronous code.

An “error” is a object you can throw to raise an exception — which could halt the program if it’s not captured and dealt with appropriately. You can create an Error object by passing an optional message to the constructor:

const e = new Error('An error has occurred');You can also use Error like a function without new — it still returns an Error object identical to that above:

const e = Error('An error has occurred');You can pass a filename and a line number as the second and third parameters:

const e = new Error('An error has occurred', 'script.js', 99);This is rarely necessary since these default to the line where you created the Error object in the current file.

Once created, an Error object has the following properties which you can read and write:

.name: the name of theErrortype ("Error"in this case).message: the error message

The following read/write properties are also supported in Firefox:

.fileName: the file where the error occurred.lineNumber: the line number where the error occurred.columnNumber: the column number on the line where the error occurred.stack: a stack trace — the list of functions calls made to reach the error.

Error Types

As well as a generic Error, JavaScript supports specific error types:

EvalError: caused by aneval()RangeError: a value outside a valid rangeReferenceError: occurs when de-referencing an invalid referenceSyntaxError: invalid syntaxTypeError: a value is not a valid typeURIError: invalid parameters passed toencodeURI()ordecodeURI()AggregateError: several errors wrapped in a single error typically raised when calling an operation such asPromise.all().

The JavaScript interpreter will raise appropriate errors as necessary. In most cases, you will use Error or perhaps TypeError in your own code.

Throwing an Exception

Creating an Error object does nothing on its own. You must use a throw statement to, you know, “throw” an Error to raise an exception:

throw new Error('An error has occurred');This sum() function throws a TypeError when either argument is not a number — the return is never executed:

function sum(a, b) {

if (isNaN(a) || isNaN(b)) {

throw new TypeError('Value is not a number.');

}

return a + b;

}It’s practical to throw an Error object but you can use any value or object:

throw 'Error string';

throw 42;

throw true;

throw { message: 'An error', name: 'CustomError' };When you throw an exception it bubbles up the call stack — unless it’s caught.

Uncaught exceptions eventually reach the top of the stack where the program will halt and show an error in the DevTools console, e.g.

Uncaught TypeError: Value is not a number.

sum https://mysite.com/js/index.js:3Catching Exceptions

You can catch exceptions in a try ... catch block:

try {

console.log( sum(1, 'a') );

}

catch (err) {

console.error( err.message );

}This executes the code in the try {} block but, when an exception occurs, the catch {} block receives the object returned by the throw.

A catch statement can analyse the error and react accordingly, e.g.

try {

console.log( sum(1, 'a') );

}

catch (err) {

if (err instanceof TypeError) {

console.error( 'wrong type' );

}

else {

console.error( err.message );

}

}You can define an optional finally {} block if you require code to run whether the try or catch code executes. This can be useful when cleaning up, e.g. to close a database connection in Node.js or Deno:

try {

console.log( sum(1, 'a') );

}

catch (err) {

console.error( err.message );

}

finally {

// this always runs

console.log( 'program has ended' );

}A try block requires either a catch block, a finally block, or both.

Note that when a finally block contains a return, that value becomes the return value for the whole try ... catch ... finally regardless of any return statements in the try and catch blocks.

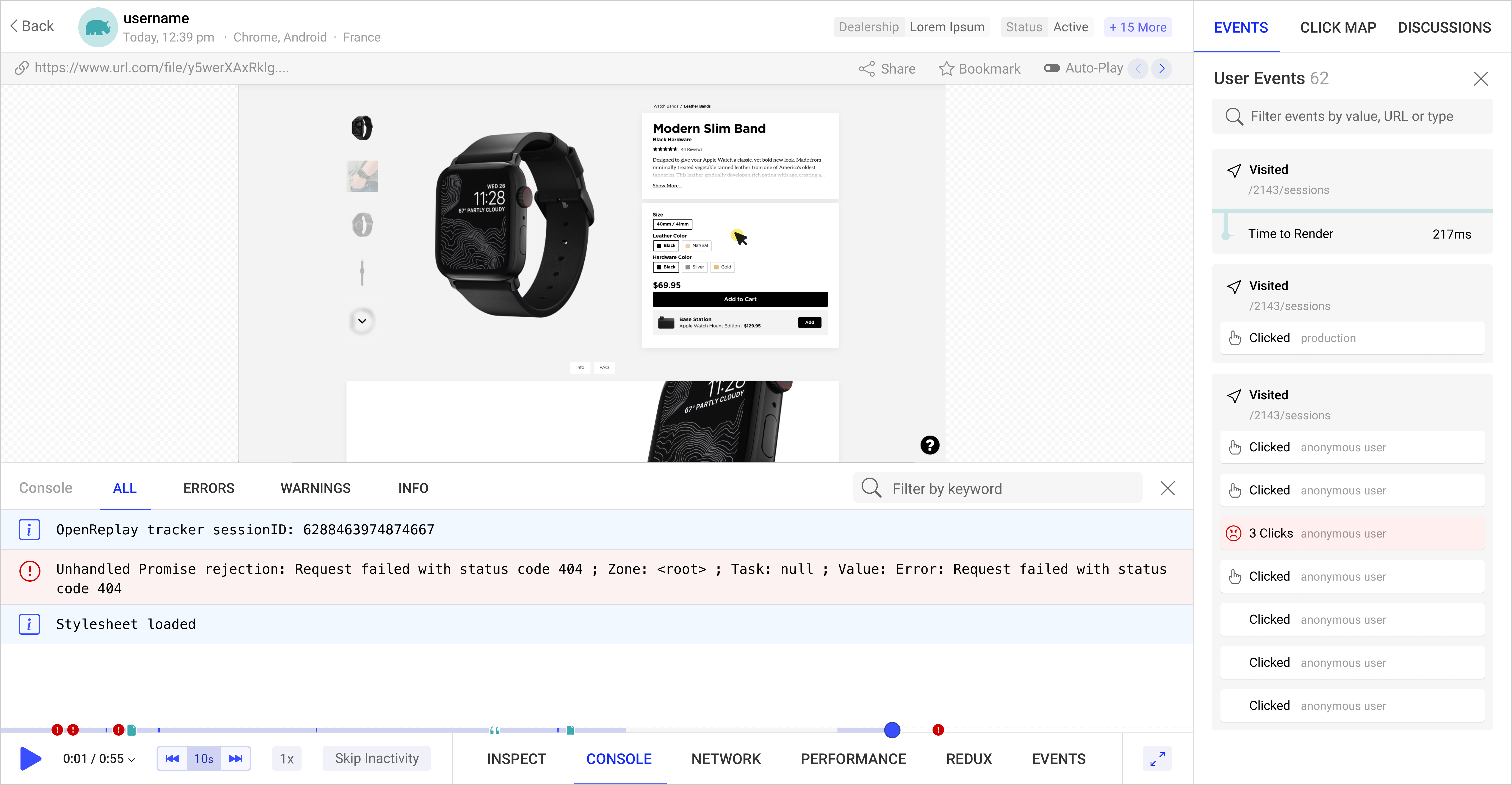

Open Source Session Replay

OpenReplay is an open-source, session replay suite that lets you see what users do on your web app, helping you troubleshoot issues faster. OpenReplay is self-hosted for full control over your data.

Start enjoying your debugging experience - start using OpenReplay for free.

Nested try ... catch Blocks and Rethrowing Errors

An exception bubbles up the stack and is caught once only by the nearest catch block, e.g.

try {

try {

console.log( sum(1, 'a') );

}

catch (err) {

console.error('This error will trigger', err.message);

}

}

catch (err) {

console.error('This error will not trigger', err.message);

}Any catch block can throw a new exception which is caught by the outer catch. You can pass the first Error object to a new Error in the cause property of an object passed to the constructor. This makes it possible to raise and examine a chain of errors.

Both catch blocks execute in this example because the first error throws a second:

try {

try {

console.log( sum(1, 'a') );

}

catch (err) {

console.error('First error caught', err.message);

throw new Error('Second error', { cause: err });

}

}

catch (err) {

console.error('Second error caught', err.message);

console.error('Error cause:', err.cause.message);

}Throwing Exceptions in Asynchronous Functions

You cannot catch an exception thrown by an asynchronous function because it’s raised after the try ... catch block has completed execution. This will fail:

function wait(delay = 1000) {

setTimeout(() => {

throw new Error('I am never caught!');

}, delay);

}

try {

wait();

}

catch(err) {

// this will never run

console.error('caught!', err.message);

}After one second has elapsed, the console displays:

Uncaught Error: I am never caught!

wait http://localhost:8888/:14If you’re using a callback, the convention presumed in frameworks and runtimes such as Node.js is to return an error as the first parameter to that function. This does not throw an exception although you can manually do that when necessary:

function wait(delay = 1000, callback) {

setTimeout(() => {

callback('I am caught!');

}, delay);

}

wait(1000, (err) => {

if (err) {

throw new Error(err);

}

});In modern ES6 it’s often better to return a Promise when defining asynchronous functions. When an error occurs, the Promise’s reject method can return a new Error object (although any value or object is possible):

function wait(delay = 1000) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

if (isNaN(delay) || delay < 0) {

reject(new TypeError('Invalid delay'));

}

else {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve(`waited ${ delay } ms`);

}, delay);

}

})

}The Promise.catch() method executes when passing an invalid delay parameter so it can react to the returned Error object:

// this fails - the catch block is run

wait('x')

.then( res => console.log( res ))

.catch( err => console.error( err.message ))

.finally(() => console.log('done'));Any function which returns a Promise can be called by an async function using an await statement. You can contain this in a try ... catch block which runs identically to the .then/.catch Promise example above but can be a little easier to read:

// Immediately-Invoked (Asynchronous) Function Expression

(async () => {

try {

console.log( await wait('x') );

}

catch (err) {

console.error( err.message );

}

finally {

console.log('done');

}

})();Errors are Inevitable

Creating error objects and raising exceptions is easy in JavaScript. Reacting appropriately and building resilient applications is somewhat more difficult! The best advice: expect the unexpected and deal with errors as soon as possible.